More in this series

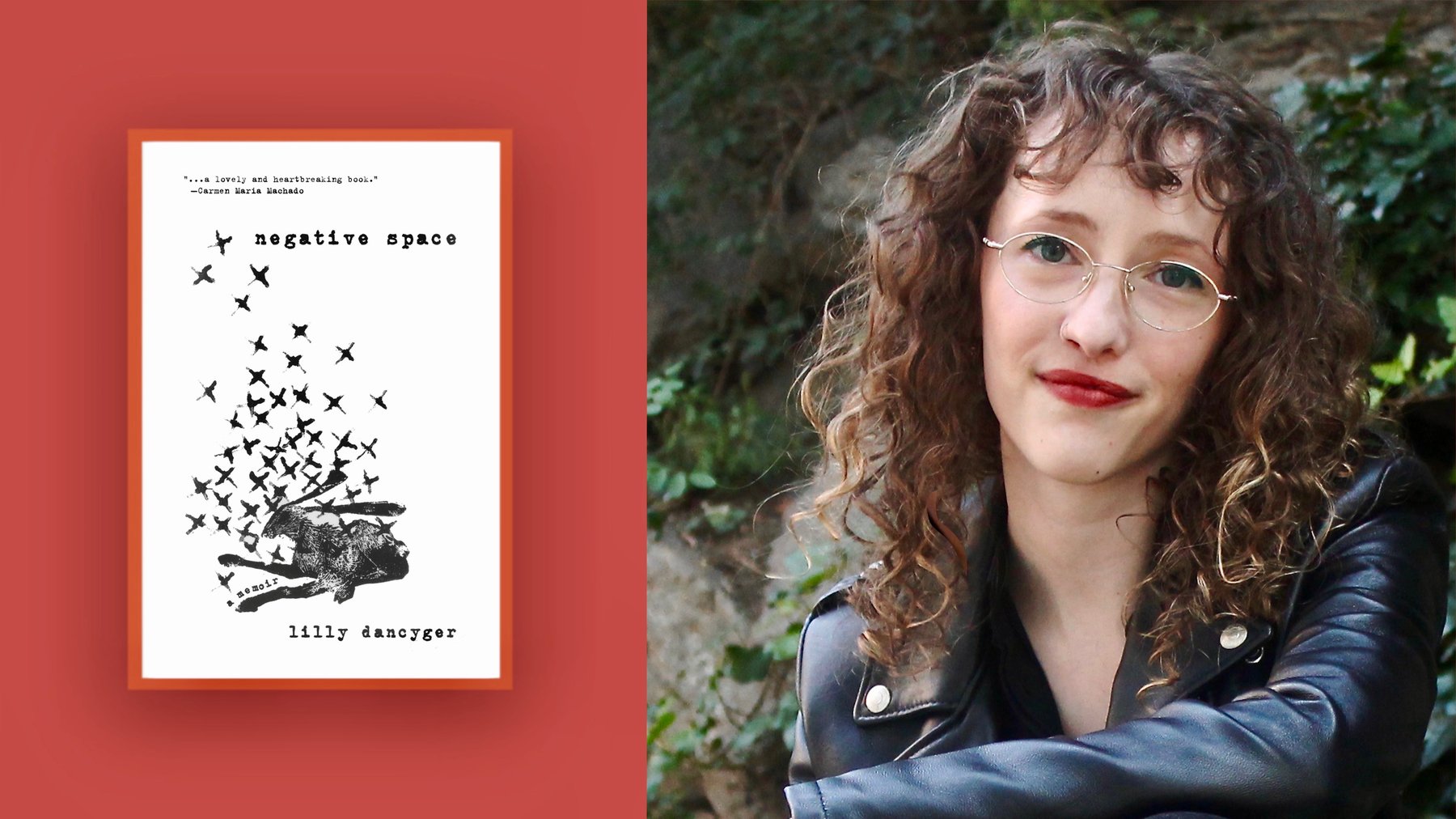

How Writing Can Raise the Dead: An Interview with Lilly Dancyger, author of ‘Negative Space’

“Describing what it feels like for somebody to not be there is a very abstract process. Pretty much this whole book has been trying to figure out how to do that.”

Negative Space

Negative Space

BarrelhouseBurn It DownNegative Space

In April, I had the privilege of speaking with Dancyger about her debut memoir. Over the course of our conversation, we talked about when to step away from a project, the difference between blame and anger, and putting loss into words.

Eliza Harris: First, congratulations on your memoir, , which has already been selected as a most anticipated title of 2021 by Electric Lit, Literary Hub, and Refinery 29. How many years have you been working on this book, and how does it feel to be on the other side of writing it?

EH: After working on for over a decade, how did you know when it was done?

EH: Do you have any advice for a writer who’s been working on the same project for many years and is starting to lose faith in it?

EH: Part of what I find really exciting about is that it’s not easily classifiable. It’s part memoir, part journalism, and also a visual narrative. What did combining these genres allow you to do that they couldn’t separately?

EH: is of course your story, but through combining these genres you’re also able to tell the story of your late father, artist Joe Schactman. Are there any specific considerations that you feel like you had to take into account when telling somebody else’s story, especially a close family member?

Needing some time away from the project doesn’t mean that you’re abandoning it.

EH: In you describe being faced with truths about your father that contradict your own memory, and, in response, you write, “I realized that this reality wasn’t any stronger than the one in my memory. I may have been able to learn more about who he was as a man, but even the ugliest truths wouldn’t change who he was to me as my father.” I was so compelled by your portrayal of truth and memory as existing simultaneously, even when they seem to conflict. Did writing your memoir change how you thought about the “truth” of the past? How do you navigate wanting to tell a true story while relying on memory?

EH: At the same time, you describe writing as a spell through which you’re able to conjure your father and have a relationship with him beyond mourning his absence. What do you think gives writing the power to not just articulate grief but, as you write, “raise the dead?”

EH: I think the way that you write about grief in this book will push against many people’s misconceptions of grief as a linear process and singular emotion. Can you talk more about the experience of trying to put loss into words

not

EH: Anger is another experience that you capture beautifully in . Particularly, you render the complexity of loving someone struggling with addiction, feeling anger at the choices they’ve made while understanding addiction as “the furthest thing from deliberate choice.” Your previous book, , is a collection of essays by women about anger. Could you talk a bit more about your interest in, and experience of, writing about anger, for either of these books?

Burn It DownNegative Space

EH: In , you also describe feeling anger toward institutions of education, from the time you dropped out of high school through pursuing your master’s in journalism. Currently, you teach a number of narrative nonfiction classes for Catapult, including one six-week class on creating a memoir outline. Did these negative experiences as a student impact how you teach?

EH: For your memoir outline class in particular, how do you help students find the collection of moments that will translate their life into a great story?

You can decide not to blame someone, to not hold it against them, but you can still feel anger for how you were affected.

EH: Outside of the writing workshops you teach, how are you finding writing community during this time of isolation?

EH: I think for a lot of people right now, Twitter is both our Achilles’ heel and saving grace.

EH: [laughter] I just have one last question for you. What is next on the horizon for you?

Eliza Harris is an editorial assistant for Catapult, Social Media Manager + Assistant Poetry Editor for DIAGRAM, and Director of Communications for The Speakeasy Project. She grew up in Durham, North Carolina, and is now based in Seattle, Washington. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @elizaeharris.

Enter your email address to receive notifications for author Eliza Harris

Success!

Confirmation link sent to your email to add you to notification list for author Eliza Harris

More by this author

2023 Submission and Freelance Writing Opportunities

Here’s a full list of submission and freelancing opportunities we’ve shared in 2023, updated twice a month. Bookmark this list to stay up to date on new postings!

What Is Book Production?

A roundtable discussion with the production department of Catapult books.

10 Poetry Contests to Enter Now

These 2023 poetry contests include grand prizes up to $5,000.